No products in the cart.

August 29, 2025

August will soon be over and so this summer is slowly but surely coming to an end. Overall, it was rather slow for me, with its rolling heatwaves. But the summer started with a break on the Costa Brava, which inspired me.

Today I have to smile a little when I think about how I tried to decide which art materials to take with me to Spain. It's not that easy. After all, you want to have what you need with you, but you don't want to pay for excess baggage.

Of course, I'm not alone in this. Wherever artists come together, whether in person or online, whether professional or amateur artists, tips are exchanged in the summer and people discuss what they need and whether they need it at all.

In any case, I wondered whether this has always been the case. Paintings like the cover of this article (by the way, Max Liebermann, On the beach at Noorwijk) capture the incomparable holiday mood. For me, art and travelling are inextricably linked. It's clear that I want to know more about it. So let's get to researching.

Artists have actually almost always been on the move. Even in ancient times, they travelled wherever there were commissions. In the Renaissance and Baroque periods, Italy was the place of longing par excellence for artists. Of course, Italy also has a lot to offer. Ruins, landscapes, the special light ... For artists, the greatest attractions were the works of the Old Masters, which could only be admired there.

Travelling back then was mainly educational. People travelled to see the world, learnt about the customs and cultures of other countries and marvelled at the treasures and works of art of the finer world. Anyone who was anyone travelled to Rome, Florence or Venice. Like so many other things, daughters were not allowed this privilege back then. But for sons from upper-class families, the Grand Tour was part of the compulsory programme in the 17th and 18th centuries.

The young men were enchanted by the beauty and took home sketchbooks full of impressions, ideas or even entire works of art. Travelling was not only about bringing back impressions, but also about distributing ideas. Art could wander, change and give rise to new centres elsewhere.

The Grand Tour contributed to the spread of artistic styles, architecture and knowledge in Europe. Sketches and studies made in Rome or Florence later found their way into workshops north of the Alps. Even furniture, gardens and urban architecture were characterised by Italian features. Flanders, for example, became an artistic stronghold in the 17th century because the knowledge it brought with it was combined with local traditions.

Once you had seen the light in Venice, you looked at the sky differently at home. Those who had marvelled at ruins got a different sense of history. And those who had learnt about foreign customs and cultures didn't come back quite the same as when they left. Travelling was good for the mind, the spirit, the body - and for the personality. Incidentally, this is still the case today if you do more than just sunbathe on the beach in your holiday destination.

Camille Pissarro, View on the Côte Saint-Denis, Pontoise, Städel Museum, Frankfurt

The Renaissance and the 19th century are real tipping points in art history, when almost everything shifts: the world view, social structures, the role of artists, themes and techniques. I always write about this in my articles. This time is no different.

The advent of the railway was a revolutionary technical development that opened up a whole new chapter in travel. But it wasn't just that you could now travel faster and further. The railway had more of an impact on people's lives than you might think today.

With the start of industrialisation a few decades earlier, many people moved from the countryside to the cities because factories were being built there. Cities like Manchester or Berlin grew explosively. But factory work was completely different from working in the fields or in the workshop. Suddenly there were fixed working hours, machine rhythms and shift work.

As a result, life became more synchronised, more strenuous, more monotonous and usually unhealthier. The cities could barely keep up with the influx. Cramped housing, poor hygiene, air pollution from coal firing. Diseases spread rapidly.

A new class of workers emerged who had little recreation in their everyday lives. At the same time, however, an urban middle class was growing that demanded education, culture and travelling in the first place. The railway increased industrialisation and at the same time created the opportunity to escape the cramped, noisy everyday life.

Previously, travelling was only possible with carriages, but these were slow. Depending on the route and road conditions, you travelled at 6-10 km/h. Travelling long distances took days or even weeks. Horses could not travel long distances in one go.

There were post stations where fresh horses were harnessed. Wealthy travellers could provide their own horses or carts along the main routes, but this was extremely expensive.

Those who did not have these means had to rely on stagecoaches. These were cramped, uncomfortable and often reeked of sweat and dust. You were at the mercy of bad roads, the weather and often robbers. Travelling was exhausting and still expensive.

Travelling for pleasure (to the city in season, to the countryside in summer and to visit relatives at Christmas) was reserved for the few who could afford to pay for horses, carriages and accommodation. But travelling spontaneously was hardly possible and the expense was only worthwhile for longer stays.

Travelling was almost never an option for poorer people. People may have travelled if they were forced to change their place of residence out of necessity (job search, emigration), but certainly not for pleasure. There was no such thing as a ‘holiday’ in the modern sense. That changed when the railway arrived.

The journey time between Liverpool and Manchester, the world's first long-distance railway line, fell from four hours to around an hour and a half. A train ticket was significantly cheaper than a carriage journey over the same distance and you were no longer squeezed in between other travellers. For the first time, people from the growing middle class - and later even workers - were able to travel for a day or a weekend to places that were previously inaccessible.

Édouard Manet, The Railway, National Gallery of Art, Washington

This gave rise to something completely new: the short excursion. On 5 July 1841, Thomas Cook organised the first publicly advertised rail excursion - from Leicester to Loughborough. Around 485 people took part, with bread, tea and musical accompaniment for the price of a shilling. Of course, the return journey was also included.

The meeting of the Temperance Movement, a temperance and reform movement, took place in Loughborough. The idea was simply to bring members from Leicester to the meeting. But this trip laid the foundations for modern mass tourism.

Thomas Cook recognised the potential of making travel affordable and plannable for many people. In the decades that followed, he offered excursions for working-class families, clubs and Sunday schools. The railway companies provided special trains and Cook took care of the organisation and catering.

He called these trips Cheap Trips - cheap excursions that were also affordable for people who would otherwise never have travelled. Day trips to the sea or the mountains were particularly popular. For many, this was their first encounter with such landscapes and was simply unimaginable before.

Initially, only Sundays or the occasional church holiday were suitable for this. But the machines in the large factories had to be serviced. Entire factories closed for a week at a time, often in summer. Workers used the time for family visits, local festivals and, thanks to the railway, increasingly for trips to the seaside.

The consequences were quickly felt on the coast. In England, seaside resorts such as Blackpool, Margate and Brighton boomed. Piers, promenades, bathhouses - infrastructure for leisure time was created, not just for spa guests. Separate bathing areas and bathing machines organised the new public beach life.

These were small, wooden changing trolleys on wheels that were pulled into the water on the beach, usually by horses. Bathers (especially women) could change in them undisturbed and enter the water directly through a small door without having to walk across the public beach in their swimming costumes. They only disappeared when mixed bathing slowly became the norm.

On the continent, too, the map of places of longing shifted. In France, Paris and Normandy were suddenly close together: The line to Trouville/Deauville was completed in 1863 and transformed the Côte Fleurie into a summer paradise for modern leisure activities.

And artists were right in the centre of it. Eugène Boudin painted elegant parties on the beach from the early 1860s. He is considered the ‘inventor’ of the beach picture. After all, elegant ladies and gentlemen in colourful dresses at coastal resorts such as Trouville or Deauville were new. Until then, hardly anyone had chosen the banal pleasure of the beach as a worthy subject.

Eugène Boudin, At the Beach, Sunset, MET, New York

Eugène Boudin was born in Honfleur, at the mouth of the Seine in Normandy, in 1824.

His father was a sailor, and the sea, harbour, sky and changing weather were subjects that Boudin would never let go of.

He was one of the first to consistently paint ‘en plein air’. Instead of composing idealised landscapes in the studio, he sat down on the beach, on the harbour, in the open air. His contemporaries called him the ‘king of the sky’ (roi des ciels) because he painted the changing moods over the sea so vividly.

The young Claude Monet came into contact with Boudin in Le Havre. Boudin encouraged him not only to draw caricatures, but also to observe the play of light outside. Monet later said that he owed a great deal to Boudin - and so do we. For who knows, without Eugène Boudin as a pioneer, Impressionism might never have existed

.

„If I have become a painter, I owe it to Eugène Boudin. ... My eyes were opened and I finally understood nature.“

— Claude Monet

In 1870, Monet and his wife Camille spent their honeymoon in Trouville. There he also painted the beach as a place for summer holidays: pleasure, leisure, fashion, light. Camille Monet and Madame Boudin sitting on the beach, fluttering dresses and parasols, other small beach scenes with walkers and the shimmering sea atmosphere.

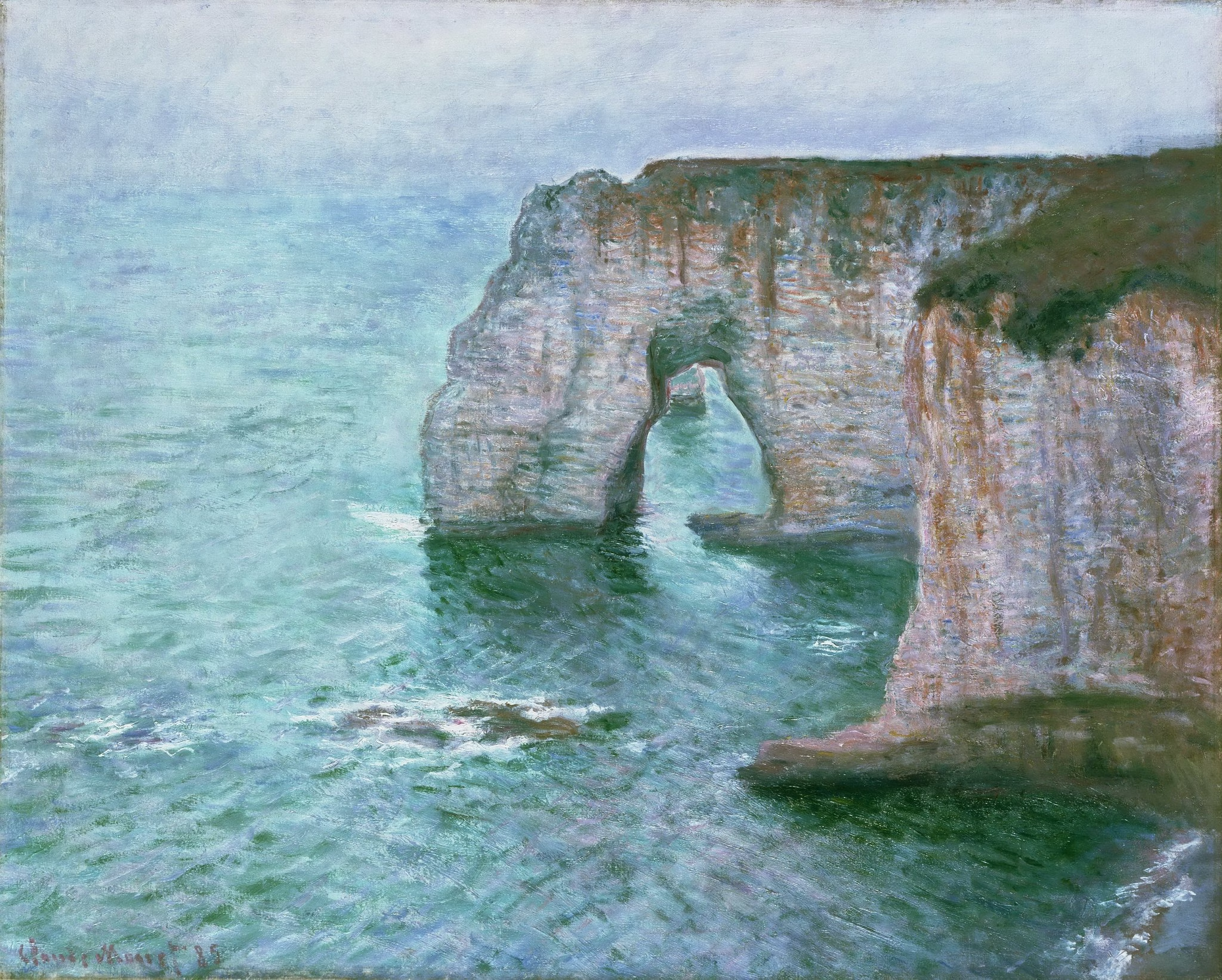

Nevertheless, Monet focussed less on social scenes and more on light, movement, and the moment. A decade later, Monet once again turned his attention to the Normandy coast, this time not to the fashionable bathers but to the rocks of Étretat. In general, people disappeared more and more from his paintings. His preoccupation with light and weather became more intense.

Monet painted the chalk cliffs of Étretat in countless variations: in sunlight, in fog, in storms, at high and low tide. The focus was clearly on nature and its changes. The coast as a sublime natural phenomenon — almost like a cathedral of stone and light.

Claude Monet, Étretat, Musée du Luxembourg, Paris

France was certainly the artistic centre in the 19th century. But summer holidays by the sea also became a theme elsewhere. Thanks to England's head start in the development of the railway, the beaches there had developed their own culture early on.

In 1858, William Powell Frith painted the Victorian seaside culture in all its facets in his large social panorama Ramsgate Sands — densely packed figures, parasols, bathers and walkers, a swarming picture of the modern seaside resort.

Beaches also became a motif on the North Sea coast. In the Netherlands and later in Germany, painters were drawn to Scheveningen and Noordwijk. Max Liebermann, for example, also captured beach and bathing scenes there, as in the cover painting. Even further north, in Denmark, an artists' colony gathered in Skagen from the 1870s onwards. Painters such as Peder Severin Krøyer depicted fishermen, bathers, and walks by the sea, flooded with light and bright.

The motif even appeared in America at almost the same time. In 1869, Winslow Homer painted Long Branch, New Jersey — elegant ladies with fluttering dresses by the Atlantic, in the same spirit of summer holidays that had also become a pictorial theme in Europe.

Winslow Homer, Long Branch (New Jersey), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

But summer holidays did not always mean the sea. The mountains had their own attraction. And with the railway, they were suddenly within reach.

German and Austrian Alpine associations organised the new way of going up into the mountains. In 1871, Europe's first cogwheel mountain railway ran on the Rigi in Switzerland. From here, the model spread further. New cogwheel and cable railways opened up the Alps, and Alpine clubs with their huts and trails made it possible to experience the high mountains. Those who had previously only read about peaks could now see them with their own eyes.

The French Alps with Mont Blanc became a destination not only for mountaineers, but also for those who wanted to marvel at the glaciers and peaks from a safe distance. Painters such as Alexandre Calame captured the Alps in imposing views. But it didn't always have to be so monumental. Artists also captured glaciers and mountain scenery more easily and directly in sketches and watercolours.

The smaller mountain panoramas of the south became a motif just as often as the mountain massifs of the Alps. Paul Cézanne devoted himself tirelessly to the Montagne Sainte-Victoire near his home town of Aix-en-Provence. Paul Guigou had also discovered the Provençal landscape for himself. In his works, he depicted nature in the south of France with villages, hills and sparse vegetation, sunlit and austere.

No heroic peaks, but an ever new encounter with form, colour and light.

Paul Guigou, Landscape by Roquevaire in Provence, Städel Museum, Frankfurt

At the foot of the mountains, the lakes beckoned. Not only were they scenic, with the sky and peaks reflected in the water, they were also a social meeting place. Steamboats, seaside resorts, lakeside promenades — the perfect place to see and be seen.

Painting picked up on this attitude to life. In addition to atmospheric landscapes, paintings were created in which boats, bathers, and lakeside houses formed the motif. The lakes were shown as natural idylls, but also as places where people spent the summer.

Whether on Lake Geneva or on the lakes of northern Italy, on Tegernsee or Attersee, everywhere the landscape was combined with the new leisure culture. Artists captured how water surfaces caught the light, how the sky and mountains blurred into the lake, and how social life became part of this backdrop.

Gustav Klimt, Castle Kammer at Attersee III, Collection Belvedere, Wien

In hot summers, it was not only the haute volée who were drawn to the shady coolness of the woods and the banks of the rivers. People spent their time in these quiet retreats on walks, picnics or horseback rides. Artists captured these moments - forest clearings, winding paths, plays of light between the trees.

Rowing boats with day trippers, couples drifting along, people looking for relaxation away from work and city life. Picnics in the forest and boat trips on the rivers in the neighbourhood were affordable, uncomplicated and at the same time ‘fine enough’ to be socially acceptable.

Painters gratefully took up these motifs. Instead of historical and mythical scenes, they wanted to show modern life. A picnic or a boat trip provided an opportunity to depict fashion, behaviour and social roles: Who sits how? Who is looking at whom? Who is standing outside? These scenes thus became almost small-scale social studies.

At the same time, these activities were exactly what people expected from a summer escape: light-heartedness, closeness to nature and socialising.

Edouard Manet, Boating, The MET, New York

The world got bigger in the 19th century. And that changed art forever. Until then, landscape had only been the location of events, but it became the main protagonist in Impressionism at the latest. Real places could be travelled to, painters depicted landscapes that actually existed and determined the mood of the painting.

The railway created the possibilities, but it was art that awakened wanderlust. Art responded to new leisure habits, but it also shaped them. Paintings of picnics, flowing dresses and imposing mountain peaks made people want to go to a river or hike in the mountains themselves. Summer holidays as a social phenomenon became visible, comprehensible and permanent through art.

The art of the 19th century was groundbreaking and the fascination with it continues to this day because we understand what we see. No encoded meaning, no need for religious or historical knowledge. This is life as we know it. Fashion has changed, the cities are bigger. But the paintings speak our language. And when we look at the light in them, they awaken the summer in us.

Join the newsletter now

and not miss a thing

Get exclusive insights into my creative processes, learn the stories behind my artwork

and receive invitations to my exhibitions and events.

To say thank you, I'll give you 10% off your first purchase.