No products in the cart.

February 19, 2025

The current global developments scare me. In many countries, authoritarian forces are gaining ground, and democratic values are under pressure. In the US, President Trump has taken measures that weaken the separation of powers, undermine the independence of the media and judiciary, and sweep human rights into the gutter. With Elon Musk as a dangerous accomplice by his side (or is it the other way around?), he is pursuing an agenda that centralizes power, intimidates political opponents, and further erodes the foundations of democracy in the US.

Across many European countries, right-wing parties are gaining strength and increasing their influence on the political landscape. Elon Musk plays a significant role here as well. On X, he is not only attempting to control public discourse, but is also deliberately constructing an alternative media ecosystem that amplifies right-wing narratives while silencing critics. Musk fuels disinformation, provides a platform for extremist voices, and undermines democratic structures—whether through his support for Trump or his efforts to delegitimize institutions like the EU and independent journalism.

In Germany, the AfD is polling at over 20 percent ahead of the federal election on 23 February—a party that has been classified as firmly far-right by the domestic intelligence service in parts. CDU leader Friedrich Merz has abandoned his previous stance of distancing himself, openly courting the far right and cooperating with the AfD in parliament. As democracy teeters, conservative politicians prefer to normalize far-right positions rather than take a firm stand against them.

Whenever societies begin to falter, radical forces thrive. Historically, it has never been times of stability that brought extremists to power. The common claim is that the shift to the right is merely a response to social discontent—but that view is too simplistic. In reality, right-wing and authoritarian movements actively pursue strategies to destabilize societies, exploiting chaos and uncertainty for their own gain.

Right-wing and authoritarian forces do not benefit from stability—they thrive on fear, division, and weakness. They know that the greater the crisis, the louder the call for a 'strong leader.' A well-worn pattern:

The more chaotic the situation, the easier it is for authoritarian forces to present themselves as the saviours in times of need.

Right-wing movements despise the EU. Why? Because the EU stands for multilateral cooperation, democracy, and shared values. A strong, stable Europe with functioning democracies and relative social security is the greatest obstacle to their ideology. That is why they actively work to undermine this stability.

When every country is fighting for itself, there can be no collective resistance against authoritarian tendencies. This is why right-wing parties deliberately push nationalism:

Far-right forces do not just seek to defeat political opponents—they aim to change the rules of the game. A strong, stable democratic system makes it difficult to seize absolute power. That is why they weaken institutions by:

The claim that German culture is under threat from migration and "leftist elites" is not about real problems—it is a deliberate strategy to stoke fear and mobilize voters.

Why? Because it works. The more people argue about culture wars, the less they focus on real politics. While voters debate whether German traditions are being "erased" by migration or whether individuals should be able to choose their pronouns—an issue that affects no one but the person themselves—right-wing politicians quietly consolidate their power behind the scenes.

These manufactured outrage debates resurface time and again—from supposedly "banned" Christmas carols in schools to demands for a "dominant culture." They serve one purpose: to distract from the real issues that politics should be addressing.

Never before has it been so easy to manipulate the masses. While traditional media (at least in theory) fact-check and maintain a certain level of objectivity, social networks have become the perfect playground for populists and demagogues.

Fake news spreads faster than reliable journalism. Algorithms push the content that generates the most outrage and fear. A sensationalist lie can reach millions—while a correction barely registers with a fraction of that audience.

People are increasingly trapped in digital echo chambers, where they only hear what reinforces their existing beliefs. Right-wing populist movements have mastered this tactic: they create parallel realities in which they are the victims, and “the others”—migrants, leftists, feminists, scientists—are the enemy. The new authoritarians no longer need to abolish free speech outright—they simply have to distort it so thoroughly that truth and lies become indistinguishable.

Far-right parties are nothing new in post-war Europe, but for decades, they remained on the fringes. Germany, in particular, believed it had learned from its past—or so we thought. Today, they have become an established political force—not just because their voter base has grown, but because conservative parties have adopted their positions.

Under Friedrich Merz, the CDU flirts with AfD talking points, echoes far-right rhetoric (“asylum tourism”), and thus shifts the political discourse further towards extremism. The barriers to racist, misogynistic, or authoritarian narratives are gradually being lowered. What was once considered a political taboo has now become an accepted campaign strategy—allowing democratic parties to drift rightward, while far-right rhetoric embeds itself deeper and deeper into the political mainstream.

Why Do I, as an Artist, Write About Politics on an Art Blog?

I often see people in forums claiming that art should be neutral. But it never was. Well, maybe back in the days of cave paintings—when people pressed their hands onto stone walls or carved hunting scenes into rock. But since the dawn of civilization, art and power have been deeply intertwined.

Rulers—whether the pharaohs of Ancient Egypt, the Catholic Church, or the Habsburgs—have always used art to legitimize their rule, glorify their victories, and etch their narratives into the collective consciousness.

But politics isn’t supposed to be about who holds power. Or at least, it shouldn't be. Politics determines how we live—what rules shape our society, what values we uphold. Our bodies, our thoughts, our way of life—everything is political.

That’s why art, in turn, cannot help but be political. Artists have always reflected the issues of their time. They have exposed injustice, questioned societal shifts, and criticized those in power—even when their art did not seem overtly “political” at first glance.

Art doesn’t have to be loud to take a stand. It doesn’t need to be overtly protest-driven to challenge the status quo. But if it refuses to engage with the world—if it reflects nothing, questions nothing, makes nothing visible—then it is nothing more than decoration.

And art has never been just decoration.

That is why authoritarian systems target art first. Whoever controls what people see, hear, and feel ultimately controls what they think. Authoritarian movements fear creative freedom—because it escapes their grasp, because it brings things into the light, and because that makes it dangerous.

At the same time, they use art as a tool of manipulation. Because to control a society, one must first control its narratives.

Those in power do not want open questions; they want definitive answers. Not uncertainty, but clear-cut stories. Not plurality, but control. That is why artists have always been among the first to come under attack when political systems begin to shift. Painters, poets, musicians, filmmakers—anyone who exposes social injustices, voices criticism, or refuses to conform becomes a threat.

Freedom of art is freedom of democracy. And when one falls, the other follows.

History is full of examples of governments attempting to suppress art or use it for their own purposes. Some have wielded the blunt force of outright repression, while others have employed more subtle methods—but the goal has always been the same: to control art in order to control society.

For a fascinating exploration of this topic, take a look at the interview with “Peter Hope (or not)” on this website.

One of the most infamous examples of art censorship is the “Degenerate Art” exhibition in Nazi Germany. In 1937, modern works by artists such as Paul Klee, Emil Nolde, Otto Dix, Hannah Höch, and Max Beckmann were publicly denounced. Their art was branded as “sick,” “non-German,” “subversive.” The reasoning was never about aesthetics. It was about power.

Modern art stood for individuality, for new perspectives, for diversity. All of this was anathema to the Nazis—then as now—because their ideology relied on uniformity and control. “Degenerate art” had to disappear to make way for monumental statues of heroes and idealized depictions of the so-called Aryan race—art as propaganda.

But the vilification of modern art was only one part of the attack on cultural diversity. As early as 1933, shortly after the Nazis seized power, the infamous book burnings took place. Works by Bertolt Brecht, Erich Kästner, Heinrich Mann, Bertha von Suttner, Sigmund Freud, and many others were thrown into the flames—because they did not fit into the Nazi worldview. Literature that encouraged critical thinking had to be erased.

Heinrich Heine’s chillingly prophetic words capture this reality with devastating accuracy:

“Where they burn books, they will also, in the end, burn people.”

Under Stalin’s Soviet Union and Mao’s China, art became a tool for maintaining power. Paintings had to depict workers in heroic poses, poetry had to praise the party, and films had to illustrate the glorious future of communism. Anything that sowed doubt was branded bourgeois, reactionary, or subversive. Artists who resisted were persecuted, imprisoned, or even killed. The message was clear: art was allowed—as long as it didn’t think.

Donald Trump has repeatedly lashed out against artists, intellectuals, and cultural figures who criticized him. Hollywood, he claimed, was “far-left,” journalists were “enemies of the people” (those who didn’t toe the line were sidelined), and the arts didn’t deserve public funding.

He had already attempted to eliminate the National Endowment for the Arts—the most significant public arts funding body in the U.S.—during his first term. Back then, he failed. But since January, his administration has significantly weakened the institution: cutting funding for diversity and social projects, shutting down politically inconvenient programs, and installing a new leadership that is steering it in a more ideologically aligned direction.

What began as a culture war under Trump (avoiding the term coup d'état) is already taking more concrete shape in parts of Europe. In Hungary, Viktor Orbán has systematically expanded his control over the cultural sector. Independent theatres and museums have been financially starved, while institutions loyal to the government have received millions. School curricula have been rewritten to emphasize patriotic values.

A similar pattern emerged in Poland, where the PiS government sought to steer arts funding in a political direction. Critical artists were excluded from state funding, while nationalist narratives were promoted. Freedom of art was not officially abolished—it was simply replaced.

This list of examples could go on indefinitely. Whenever authoritarian systems or right-wing populist governments gain influence, art is among the first targets. Sometimes it is openly suppressed, sometimes subtly redirected, sometimes defamed or starved of funding. But in the end, it is always about the same thing: control over the narrative.

This is not just a historical problem—it is a current one. And it affects all of us.

In times of political repression, art becomes an act of resistance—because it speaks the truths that cannot be spoken. Images linger in the mind, words echo long after they are read, melodies unite people across borders. Where politics often remains abstract, art creates something immediate, something emotional.

History is full of artists who refused to bow to oppressive regimes—many of whom were persecuted, banned, or censored for their defiance. And yet, it is their work that endures, becoming symbols of resistance that outlive the rulers who sought to silence them.

The painting depicts a scene from the Spanish War of Independence against Napoleon. A group of Spanish resistance fighters stands on a barren hillside. In front of them, French soldiers with rifles at the ready, prepared to execute them.

The soldiers' faces remain hidden—they are faceless enforcers of a brutal system. At the center of the composition stands a man in a white shirt, his arms raised in a gesture of defiance and surrender. He is the innocent, the martyr, the symbol of all those who dare to resist an overwhelming force—and pay for it with their lives.

The lantern casts its light directly on him—not on the soldiers, not on the background. Goya deliberately draws our focus to this moment of terror and sacrifice, making him the emotional and visual centerpiece of the painting.

Francisco de Goya | The Third of May 1808

Goya is not merely documenting a historical event—he is making an accusation. He does not portray war as a heroic struggle but as a cold-blooded execution. The powerful remain faceless, while the victims are human—full of expression, emotion, fear, and despair.

It is no coincidence that this painting has been repeatedly used as a symbol of political resistance, appearing in protests against fascist regimes and within modern peace movements. The Third of May 1808 remains a timeless reminder of the brutality of oppression—and the courage of those who stand against it.

While Goya concentrated the brutality of war into a single moment, Picasso created a complex collage of chaos, fear, and destruction. His painting was a response to the bombing of the Spanish town of Guernica by German and Italian warplanes—an attack that helped General Franco secure his fascist rule.

We see mutilated bodies, screaming faces, a mother clutching her dead child. A bull—often interpreted as a symbol of Spain—stands motionless amidst the chaos, as if the horror had already become normality. The colour palette is deliberately limited to black, white, and grey—draining all life from the scene.

Picasso’s “Guernica” / Reina Sofia, Spanish Embassy

"Guernica" is not just a war painting—it is an emotional indictment. Picasso shows war as profound human suffering.

Anecdotes claim that in 1936, a German officer in Paris looked at the masterpiece and asked Picasso, “Did you do this?”

Picasso allegedly replied, “No, you did.”

There is no solid evidence for this encounter, but as the saying goes: Se non è vero, è molto ben trovato—if it’s not true, it’s still well invented.

The phrase originates from Giordano Bruno, a doubter of religious dogma, who himself was burned at the stake in Rome in 1600 for challenging the Catholic Church. A fitting historical parallel to the fate of those who dare to question authority.

Returning to Guernica: In February 2003, shortly before the start of the Iraq War, a tapestry of the painting was covered at the UN headquarters in New York. The artwork, a loan from the Rockefeller family since 1985, hangs at the entrance to the Security Council chamber and is one of the most powerful anti-war symbols in modern history.

The covering took place during a press conference by U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell, who was presenting the case for military intervention in Iraq. Official UN spokespeople explained that the artwork’s complex background was unsuitable for television broadcasts. However, many diplomats suspected the real reason: the striking anti-war imagery of Guernica clashed too strongly with the message of an impending war and was therefore concealed.

The fact that a powerful former U.S. general and Secretary of State had to fear being exposed by a painting speaks volumes about the power of art.

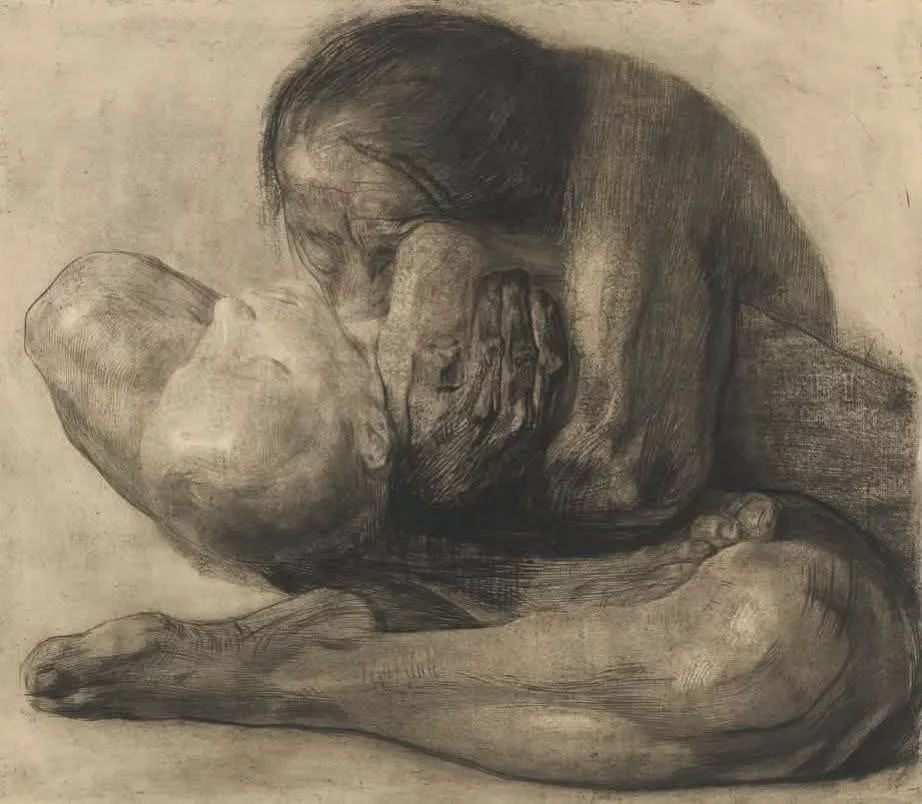

Hardly any artist has depicted the pain, grief, and despair of war as hauntingly as Käthe Kollwitz. Her works are a cry against violence, social injustice, and the human cost of war.

In 1914, her youngest son, Peter Kollwitz, volunteered as a soldier—just weeks later, he was dead.

His loss shook her to the core and shaped the rest of her artistic career. Even before that, she had been deeply engaged with social issues, focusing on the harsh living conditions of the working class. She explored themes of poverty, hunger, and oppression, as seen in her print cycles A Weavers’ Revolt (1893–1897) and Peasants’ War (1902–1908), which depict the struggles and suffering of the disenfranchised.

Käthe Kollwitz | Frau mit totem Kind

The death of her son Peter marked a profound personal and artistic transformation. This traumatic event deepened her pacifist convictions and turned her focus even more strongly toward themes of grief, loss, and the futility of war. Her work became more emotional, reflecting both her personal sorrow and a broader anti-war stance.

Her art was now infused with deep mourning—but also with rage. Rage at a system that sent young men to their deaths. Rage at militarism, which had robbed generations of mothers of their children. Her work became an indictment of a world in which the weakest always paid the highest price.

In her print series War (1921–1922), she confronted the devastation and sorrow left in the wake of conflict. The woodcuts are dark, raw, and unfiltered. There are no heroes, no soldiers in uniform—only widows, orphans, and grieving mothers.

When the Nazis seized power in 1933, Käthe Kollwitz quickly became a target. Her art was too antimilitarist, too socially critical, too uncomfortable. She was forced to resign from the Academy of Arts, her works were removed from museums, and she was banned from exhibiting publicly.

Until her death in 1945, she continued to draw—often only for herself, often just in sketches. But she refused to be silenced.

Today, her works hang in memorials and museums around the world—as a reminder and a warning.

The Question of Responsibility for the Past: Art as a Weapon Against Forgetting. In postwar Germany, the question of how to reckon with the past became a central challenge for artists. How do we remember? How do we deal with guilt? And where does forgetting begin?

Joseph Beuys confronted these questions in ways that were not always well received. His actions and installations were often unsettling, provocative—exactly as he intended.

Beuys was not a traditional moralist with a brush and canvas. He believed that art was a social process, that it had to intervene directly in life. When he famously said, “Everyone is an artist,” he didn’t mean that everyone should paint. He meant that every person bears responsibility for shaping what happens around them.

His art was never meant to be comfortable, and that is what made it so powerful.

Anselm Kiefer painted the past on a scale too large to ignore. His works are monumental, typically dark, built up from thick layers of paint and material. He uses ash, charred wood, lead—materials that evoke destruction but also transformation.

Artists around the world take on this responsibility, and not just in painting or performance art. The song Blowin’ in the Wind by Bob Dylan, later a Nobel laureate, became an anthem of the American civil rights movement. With seemingly simple questions (“How many roads must a man walk down?”), the song exposes the hypocrisy of a society that claims to uphold freedom while maintaining systemic racism. And Bella Ciao, originally an Italian partisan song, became a symbol of anti-fascist resistance—sung at protests worldwide to this day.

George Orwell’s 1984 presents a dystopian world where language is manipulated, history is rewritten, and thoughts are monitored. Whenever surveillance laws tighten or disinformation becomes a weapon, the novel resurfaces in public debate. Bertolt Brecht used theatre as a political tool, deliberately breaking the illusion of storytelling. He had actors step out of character, addressing the audience directly—because he wanted them to think, not just be entertained.

Brecht himself called this the Verfremdungseffekt—the alienation effect. A technique through which art forces us to see reality from a new, unfamiliar angle, allowing audiences, readers, listeners, and viewers to uncover hidden aspects of the world around them.

The art of resistance has evolved – but its essence remains the same. Not only artists like Ai Weiwei and Banksy demonstrate that art continues to be a sharp instrument in the digital age. Protest no longer takes place solely in museums or on the streets – it unfolds in real-time, online, visible to the entire world.

Countless known and unknown artists use their work to amplify marginalized voices, raise awareness about mental health, fight against racism, or bring the climate crisis into focus. Their art speaks of personal pain and collective struggles, of resistance and hope.

A society without art is a society without memory, without critique – and without a future. We need these voices; they serve as a corrective, a counterpoint to what is sold to us as inevitable. Especially in times of political upheaval and societal division.

Art must not remain silent. It reminds us that resistance is possible – and that it remains necessary.

Join the newsletter now

and not miss a thing

Get exclusive insights into my creative processes, learn the stories behind my artwork

and receive invitations to my exhibitions and events.

To say thank you, I'll give you 10% off your first purchase.