No products in the cart.

September 19, 2025

I have a real weakness for heist and art theft films. Pierce Brosnan's nonchalance as Thomas Crown, the teamwork in the Ocean films, or the wit and chemistry of Audrey Hepburn and Peter O'Toole in How to Steal a Million: art theft – that sounds like safes, disguised getaway cars and perfectly timed plans. I can't resist it.

In reality, art thefts are often far less glamorous and sometimes surprisingly unspectacular. But there are robberies in art history that sound so improbable that they could just as well have come from a screenplay. I would like to present three of them today.

Incidentally, when it comes to stolen art, there is one name that comes up again and again – Vincent van Gogh. Hardly anyone else has been stolen from so often. His paintings disappeared from museums, reappeared in mafia hideouts or were simply left behind in cars. There are several reasons why Van Gogh has become the favourite victim of art thieves worldwide.

Vincent van Gogh was incredibly productive. Although he only lived to be 37 and did not start painting until he was 27, he left behind almost 900 paintings and over 1,000 drawings. So it's no wonder that he must be one of the most stolen artists in percentage terms. But his works are also among the most valuable in the world, and everyone immediately recognises his name. This makes his paintings attractive to thieves, even though they are practically unsellable.

Perhaps it also has something to do with the fact that van Gogh poured his vulnerability into his paintings, and that art thieves unconsciously recognise this and therefore often choose them. Who knows?

In any case, there are repeated break-ins at smaller and larger museums in order to get hold of Van Gogh's masterpieces.

Most recently in March 2020, during the coronavirus lockdown, when Van Gogh's Spring Garden (also known as The Parsonage Garden at Nuenen in Spring) was stolen from the Singer Laren Museum in the Netherlands. The painting was found in 2023 in Amsterdam at the home of a former art thief and returned. I'm not telling that story today, but Van Gogh also plays a role in one of my three robbery stories.

It is the morning of 27 April 2003. The staff at the Whitworth Art Gallery begin their rounds of the rooms to prepare the museum for the day. The Margaret Pilkington Room is part of the main exhibition. Here, the gallery displays works on paper from its collection, and here the staff come across three empty frames on the wall.

The police are called immediately. Everything indicates that the thieves specifically selected the three works. They are The Fortification of Paris with Houses by Vincent van Gogh, Poverty by Pablo Picasso and Tahitian Landscape by Paul Gauguin. The Whitworth Art Gallery specialises in works on paper and has a large collection of prints, drawings and watercolours (including Turner, Blake and Hockney). But Van Gogh, Picasso and Gauguin are, of course, the biggest ‘drawcards’ in the international ranking.

Although these are neither the artists' greatest masterpieces nor the most expensive works in the gallery's collection, they are undoubtedly among the best known and most popular exhibits. It is therefore hardly surprising that the theft has caused such a stir in the city. Even before further details are known, the first media outlets are already reporting a ‘serious art theft’ and a ‘catastrophe for Manchester’.

The British press speaks of a ‘devastating loss’ and an ‘irreparable blow’ to the Whitworth Art Gallery. Some headlines suggest that the paintings have probably already been smuggled out of the country or are gone forever.

But just a few hours later, the police receive an anonymous tip. They search a public toilet that is out of order in Whitworth Park, right next to the museum. And sure enough, they find a cardboard tube containing all three works – and a note with the message:

The intention was not to steal but to highlight the woeful security.

The relief is immense. However, as all three works are watercolours on paper, storage in the cardboard tube and the damp environment caused slight damage such as watermarks, warped paper and small tears.

The works are taken to the restoration workshops at the Whitworth Art Gallery. After a few months, they are ready to be exhibited again.

The combination of shock and curiosity has made the theft headline news beyond Manchester and into the international press. Newspapers in Europe and the USA reported not only on the theft, but also on the unusual ‘return’ and the embarrassment for the museum's security system. This was then, of course, improved, although understandably no further details are known.

Harpers Ferry in West Virginia is a small town at the confluence of the Shenandoah and Potomac rivers. The town is historically known for John Brown's slave rebellion (1859) and also played a role in the Civil War. The town and surrounding countryside together form Harpers Ferry National Historical Park.

This historic town with its antique shops is a tourist attraction. The small markets that take place regularly are popular with collectors because you can always find nice pieces there.

In 2009, a woman from the neighbouring state of Virginia visits the Harpers Ferry flea market. She strolls through the market. Here and there, something catches her eye. Among other things, she is interested in a frame. It is nothing special, but pretty and decorative. At the end of the day, she takes home a small box with her purchases. Among them is the frame (including the painting). In total, she spent £7 at the flea market that day.

She keeps the painting for three years. Perhaps it hangs on her wall, perhaps it gathers dust on a shelf. In 2012, she decides to sell it. An old oil painting in a decorative frame is sure to fetch a little money at auction as a nice decorative piece or antique painting by an unknown artist, certainly more than $7.

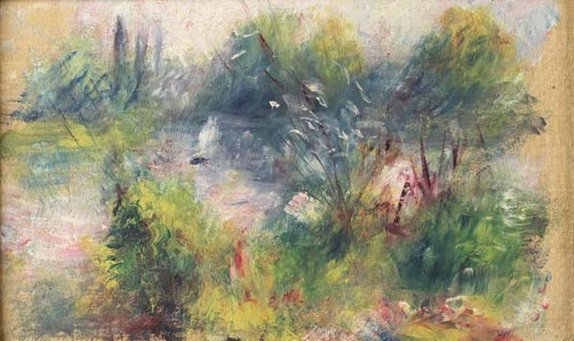

In the USA, many regional auction houses also accept everyday objects, jewellery or furniture, not just fine art, and so the painting eventually ends up at the Potomac Company in Alexandria. There it is to be auctioned. In the course of the preparations, the experts catalogue and examine the work. And that's when they get a big surprise. The inconspicuous painting in the inconspicuous frame is a genuine Renoir! Estimated value: $75,000–100,000.

Auguste Renoir, Paysage Bords de Seine, Baltimore Museum of Art

However, it will not be sold for this amount. As it turns out, it was stolen from the Baltimore Museum of Art in 1951. The painting Paysage Bords de Seine was bequeathed to the museum in 1937 by the collector Saidie May. She was one of its important patrons.

In 1951, the small Renoir painting disappeared from an exhibition. Whether it disappeared overnight or during opening hours is not clearly documented. The painting is very small (14 × 23 cm, oil on canvas), so it would have been relatively easy to remove it and hide it under a coat or in a bag. But whether that is what happened...?

The case was reported to the police, but never solved. The painting has been considered lost ever since. How it got from the museum to the flea market remains unclear to this day. Neither the perpetrator nor the whereabouts of the painting could ever be traced.

Since the painting was proven to be stolen, it legally still belonged to the Baltimore Museum of Art. The flea market visitor was therefore unable to keep it. Even though she had bought the painting in good faith, she received neither a finder's fee nor compensation. She was not even reimbursed for her £7.

After its return in 2014, the painting was returned to the Baltimore Museum of Art. There it is part of the Saidie May Collection, to which it originally belonged.

In 1934, a robbery at St. Bavo's Cathedral in Ghent shook not only Belgium but the whole of Europe. Two panels from Jan van Eyck's famous Ghent Altarpiece were stolen. The work is considered a turning point, a monumental masterpiece that heralded the Northern Renaissance.

On the night of 11 April, witnesses saw the shadowy figures of two people placing flat objects in their car. The next morning, during his morning rounds, the sacristan Van Volsem discovered that the door to the Vijd Chapel, where the altar was located, had been broken open. His immediate fears were confirmed.

The two panels, John the Baptist and The Just Judges, had disappeared. Instead, there is a note (in French) on the frame with the message ‘Taken from Germany under the Treaty of Versailles.’

During the First World War, the altar had been confiscated by the Germans and taken to Germany. The Treaty of Versailles of 1919 stipulated that Germany had to return the altar to Belgium. So is there a political connection?

Nothing happens for 19 days. Although the country is in turmoil, the police find neither fingerprints nor other clues despite extensive investigations. But at the end of April, the Bishop of Ghent, Honoré Coppieters, receives a letter. In it, the thief or thieves demand a ransom of one million Belgian francs, threatening to destroy the panels if their demand is not met. The letter is signed D.U.A.

Bishop Coppieters is prepared to pay the ransom. For him, preserving the altar as a sacred object in the cathedral is paramount. However, the Belgian government is strictly opposed to this. It does not want to give money to criminals or encourage copycats.

The blackmail letter also contains instructions for encrypted communication via the Brussels newspaper ‘La Dernière Heure’. In this way, the bishop continues to negotiate with the blackmailers and asks for guarantees.

Can you already sense the Hollywood vibe in this story? And that's not all – and every word is true!

So, after some back and forth and several letters from the thief or thieves and newspaper advertisements from the bishop, the thief or thieves are actually willing to show their good will. With the next letter, they also send the collection slip for the luggage storage at Brussels North station. And there, left by a man with a goatee, is the panel depicting John the Baptist.

![Christus[23] mit Maria und Johannes dem Täufer Kopie Der Genter Altar, ein berühmter Kunstraub](https://leafinke.de/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Christus23-mit-Maria-und-Johannes-dem-Taeufer-Kopie.png)

Ghent Altarpiece: Mary, God the Father and John the Baptist (right).

A few days later, another letter arrives with instructions and a torn newspaper page. The ransom is to be deposited at the Meulpas rectory, a courier will come to collect it, and the second half of the newspaper page will be his distinguishing mark – real film material, right?

In any case, that's exactly how it happens. A taxi driver arrives, he has the scrap of newspaper and takes the package with the ransom money. So you might think, all's well that ends well. But the police thought that returning the plaque was a sign of weakness. So instead of a million, they put only 25,000 francs in the package.

Unsurprisingly, this does not meet with enthusiasm from the perpetrator(s). Messages are exchanged again, but ultimately remain unsuccessful. On 1 October 1934, the last letter arrives at the Bishop of Ghent. The panel of the just judges remains missing.

Scene change. Six weeks later. Flemish businessman, lay preacher and former bank employee Arsène Goedertier gives a speech at a political party meeting in Dendermonde. Shortly afterwards, he collapses with a heart attack. He is quickly taken to his brother-in-law's nearby house. While someone is sent to fetch the doctor, Goedertier says: ‘I alone know where the altarpiece is. No one else knows.’

His condition worsens. His friend, notary Georges de Vos, is with him. Goedertier whispers his last words in his ear. ‘In my desk… keys… cupboard… health insurance folder…’ Then he dies.

After his death, his office is searched and the folder is found. It contains copies of the 13 blackmail letters sent to the Bishop of Ghent. But there is no trace of the painting The Just Judges.

This story contains more than enough to make this robbery a legend. Generations of treasure hunters have since searched Wetteren, churches, graves, cellars, parks, and even canals for the lost painting. To this day, it has not been found, even though rumours of a hot lead crop up from time to time.

In 1945, the painter Jef Van der Veken created a copy, which can still be seen in the altar today.

But even then, the story of the altar is not over. When World War II looms in 1939, the Ghent Altarpiece is first dismantled and taken to various locations in Belgium for safekeeping to protect it from destruction or theft. After the German invasion, the altar falls into the hands of the Nazis. It is on Hitler's ‘special list’ for the planned Führer Museum in Linz.

The Nazis confiscated the altar and took it to Neuschwanstein, later to Austria. From 1943 onwards, the situation in the war changed dramatically. The Allies increasingly bombed German cities and industrial facilities. This increased the risk that stored looted goods could also be destroyed.

The Nazis began to store the most valuable pieces in salt mines. In addition to the Ghent Altarpiece, Michelangelo's Bruges Madonna and paintings by Vermeer, Rembrandt and Rubens were also stored in Altaussee.

In May 1945, Allied art protection officers (‘Monuments Men’) discovered the holdings in Altaussee, more than 4,700 works of art!

So art theft sometimes really does resemble a heist film. Sometimes even more chaotic, absurd and mysterious than in Hollywood.

Join the newsletter now

and not miss a thing

Get exclusive insights into my creative processes, learn the stories behind my artwork

and receive invitations to my exhibitions and events.

To say thank you, I'll give you 10% off your first purchase.