No products in the cart.

December 18, 2024

It was a time of discovery, exploration, and rediscovery – in art, science, and thought. Three giants embodied this era of creativity like no others, shaping the very soul of the Renaissance: Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo Buonarroti, and Raffaello Sanzio.

For the visionary Leonardo, art and science were inseparably intertwined. Michelangelo, driven by relentless passion, created masterpieces that pushed the boundaries of what was possible. And Raphael captured the beauty of the world with an effortless sense of harmony.

What united them, what set them apart – and why does their art still move us centuries later?

In the Renaissance, harmony was more than just an aesthetic ideal – it was a philosophical concept. The rediscovery of antiquity revived the belief that beauty was a reflection of a higher order, a symbol of the divine and humanity’s pursuit of perfection.

Artists like Raphael embraced the ideas of proportion, symmetry, and balance found in ancient writings, such as those of Vitruvius and Plato. Through clear compositions, a subtle colour palette, and the emotional depth of his figures, Raphael’s works evoke a sense of unity, where everything is interconnected – the earthly and the divine, the past and the present.

Raphael’s Madonna paintings stand out for their sense of movement and humanity, distinguishing them from earlier depictions of the Virgin Mary. Unlike the often rigid and symbolic Madonnas of the Gothic period, Raphael’s figures appear alive and emotionally tangible. The fusion of human warmth with traditional iconography was groundbreaking in the Renaissance – a tender gaze, a gentle smile, or the suggestion of movement, combined with the soft transitions of skin tones (the incarnato) and subtle gradations of light, lends his figures a lifelike presence without descending into excessive drama.

The Sistine Madonna is a prime example: Mary appears not just as a saint but as a mother. Her posture is calm and serene, yet the slight sway of her body, her gaze extending beyond the viewer, and the Christ Child nestled in her arms bring movement and depth to the scene. Raphael achieves this through masterful composition: the diagonal line between Mary and the child creates dynamism, while the placement of the surrounding figures provides stability. Warm, soft tones dominate, enriched by light that adds dimension and depth. This blend of symmetry and vitality transforms the Madonna into a symbol of harmony, uniting the divine and the human in perfect balance.

Sistine Madonna | Raphael | Old Masters Picture Gallery – Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

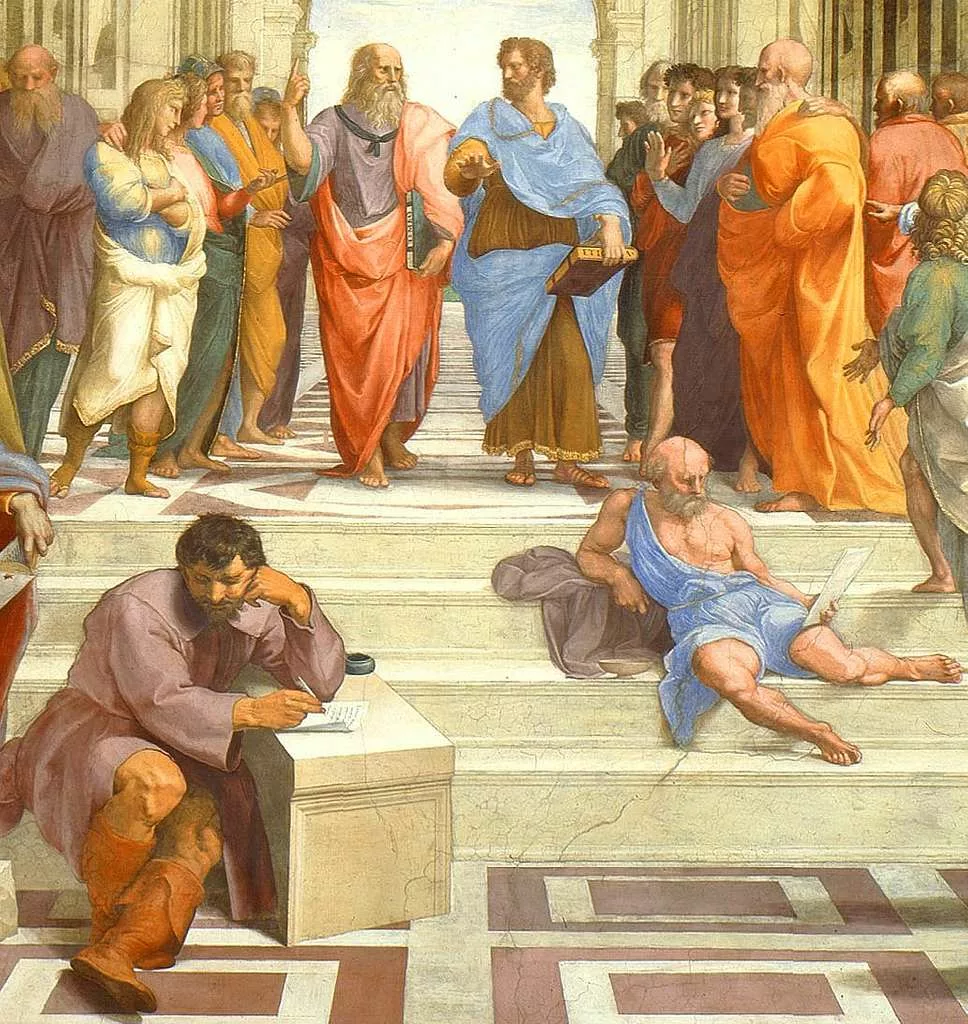

With The School of Athens, Raphael created one of the most significant frescoes of the Renaissance. Located in the Stanze of the Vatican, the work depicts an imagined gathering of the greatest philosophers and scientists of antiquity – a celebration of the human spirit and intellectual diversity. It unites movement, order, and intellect in perfect harmony.

At the centre of the composition stand Plato and Aristotle, their gestures symbolizing the two principal currents of thought: Plato points to the heavens, a reference to his metaphysical ideas, while Aristotle gestures toward the earth, emphasizing his focus on the empirical world. Their presence forms the heart of the fresco, around which the other philosophers and scholars are grouped – a symbol of how differing approaches and ideas can come together to form a harmonious whole.

The architecture in the background is more than just a backdrop; it plays a vital role in the composition. The vanishing lines of the classical arches guide the viewer’s eye toward the central figures, while the symmetrical arrangement of the groups creates a sense of structure that never feels rigid. Whether in groups or alone, the figures are depicted in lively discussion, deep thought, or expressive gestures, keeping the composition dynamic and full of life.

Raphael masterfully embodies the principle of “unity in diversity”, a core idea of Renaissance humanism. Each group appears self-contained, yet remains an integral part of the larger entire. Every philosopher is characterized with individual traits: Diogenes reclines casually on the steps, Heraclitus appears lost in thought, and Pythagoras immerses himself in mathematical studies.

The School of Athens (detail) | Raphael | Vatican Museums

Raphael's workshop in Rome was a hub of Renaissance art, exceptionally well-organised and one of the largest of its time. He led a team of highly skilled assistants and pupils who worked under his guidance. Raphael's gift for creating harmony extended beyond his artwork and into the structure of his workshop, enabling him to complete an impressive volume of commissions, including frescoes, paintings, and architectural projects.

The fact that Raphael trained pupils is not merely a footnote in his career but a central part of his legacy. He not only produced his own masterpieces but laid the groundwork for artistic continuity that extended far beyond his lifetime. His workshop became a model of artistic excellence and effective knowledge transfer, setting him apart from many of his contemporaries. Raphael's influence resonated through generations, inspiring artists such as Titian and Rubens, who admired his clarity of vision and mastery of composition.

Self-Portrait | Raphael | Uffizi Gallery | Florence

Michelangelo's works depict humanity as creative, struggling, suffering, and triumphant. They radiate power, not as a mere physical attribute, but as a pursuit of greatness, emotional depth, the breaking of boundaries, and the creation of something that transcends human existence.

Michelangelo was only 20 years old when he completed his famous Pietà. The sculpture depicts the Virgin Mary holding the lifeless body of Christ in her arms, immediately after the crucifixion. It is one of Michelangelo's earliest masterpieces and the only work he ever signed with his name.

Mary radiates both sorrow and quiet acceptance. She cradles her son’s body, yet her expression shows no distorted grief. Here, Michelangelo’s ability to convey power lies not in dramatic gestures or excessive emotion but in the subtle tension of Mary’s posture.

One hand supports Christ with maternal tenderness, while the other opens outward, as if acknowledging the divine significance of the moment. Michelangelo presents Mary not only as a grieving mother but as a mediator between God and humanity. This delicate balance between strength and serenity is what makes the Pietà so profoundly moving.

Pietà | Michelangelo Buonarroti | St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican

Despite Mary’s monumental size, which was necessary to support the lifeless body of Christ, the sculpture does not appear unnatural. Michelangelo achieves this through the masterful draping of her garments, which harmoniously integrate her volume into the overall composition.

Christ lies in a position that conveys both his weight and his brokenness. His muscles are relaxed, his head falls back – Michelangelo portrays the inevitability of death with heart-wrenching realism. Yet, at the same time, Christ’s body does not seem weakened but retains a sense of strength. The perfectly rendered anatomy, the tension in his limbs, and the details such as the crown of thorns and the wounds create a paradoxical blend of fragility and power.

Where the Pietà demonstrates the power of emotional expression, David stands as a testament to physical strength and mental discipline. Michelangelo depicts David in the moment just before his triumph over Goliath – fully focused, muscles taut, and ready to act. The details, from the veins on his hands to the tension in his tendons, are so lifelike that one might almost expect him to move at any moment.

David is not merely a portrayal of a biblical hero but a symbolic figure of the Renaissance. He embodies the triumph of intellect over brute force and reflects the ideal of the “Homo universalis” – the individual who achieves greatness through reason and discipline.

For Michelangelo, sculpting was not an act of creation from nothing but one of discovery. To him, the artist was a tool, revealing God’s creation – a spiritual calling. This concept is beautifully reflected in one of his most famous quotes:

"I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free."

Whether Michelangelo truly uttered this phrase remains historically uncertain, as it was only recorded later. Yet it perfectly encapsulates his approach to art and his revolutionary relationship with stone. Michelangelo often selected marble blocks that other artists deemed unusable, skilfully incorporating their natural forms and imperfections into his figures.

David is a prime example: the 5.17-metre marble block had been rejected over 40 years earlier by two other sculptors, who considered it too narrow and flawed. Michelangelo, however, accepted the challenge and transformed it into one of the greatest masterpieces in the history of art.

The ceiling frescoes of the Sistine Chapel were a tour de force in every sense – physically, emotionally, and artistically. Michelangelo, who considered himself more of a sculptor than a painter, spent four years working on this monumental project. He created not merely a series of impressive images but an entire world filled with drama, spirituality, and movement.

The Creation of Adam | Michelangelo | Sistine Chapel, Rome

The most famous section, The Creation of Adam, depicts the powerful gesture of God reaching out with an extended finger to bring life to Adam’s lifeless body – a striking representation of divine energy transferring to humanity. Yet Michelangelo’s mastery extends beyond this iconic scene. The frescoes capture the struggle between good and evil, the dynamism of creation, and the tensions inherent in the human condition.

Michelangelo's relentless pursuit of perfection was both a blessing and a curse. His art reflects this inner struggle – he wrestled not only with the material but also with himself. Known for his intensity and refusal to compromise, Michelangelo often worked alone, for hours on end, becoming completely absorbed in his projects.

This unwavering dedication earned him admiration but also led to conflict – especially with his patrons. Michelangelo had a notoriously fraught relationship with Pope Julius II, for whom he created the unfinished tomb, and with Pope Clement VII, who commissioned him to paint the Sistine Chapel. Both demanded much of him, and Michelangelo often resisted their expectations when they clashed with his artistic vision.

His relationships with other artists were no less complex, particularly with Raphael. Michelangelo had little regard for Raphael’s works, which he saw as too pleasing, too polished. For Michelangelo, art was born of inner struggle and passionate creation – something that required time, effort, and suffering. By contrast, Raphael’s art seemed effortless, almost playful. Beyond aesthetic differences, Michelangelo also viewed Raphael as a threat to his own position as the pre-eminent artist of the Renaissance.

The Renaissance was driven by a collective pursuit of greatness – a desire for a new and better world. People sought to push beyond the known, to discover new horizons in art, science, and philosophy. Leonardo da Vinci embodied this ambition. His works shattered the boundaries of his time.

Leonardo believed that understanding the world and creating art were inseparably linked. His relentless curiosity drove him to design machines, analyse the movement of water and air, and study human anatomy.

These anatomical studies, which involved dissecting cadavers, enabled Leonardo to depict the human body with an unprecedented level of precision for his time. Muscles, tendons, and movements in his paintings appear so natural that they seem almost alive.

In his famous drawing The Vitruvian Man, Leonardo combines the principles of geometry and mathematical laws with the human body. He shows how everything is harmoniously interconnected. This understanding of proportion and movement permeates all his works.

Vitruvian Man | Leonardo da Vinci | Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice

The Mona Lisa, painted between 1503 and 1506, is regarded as one of the most famous paintings in the world. Her enigmatic smile has captivated generations of viewers.

With the Mona Lisa, Leonardo set new standards for portraiture. In the 15th century, portraits were often stiff and formal, with sitters depicted in frontal or profile views. Leonardo, however, introduced a new dynamism and vitality to the portrayal: the Mona Lisa is turned slightly to the side, seated in a relaxed yet upright posture. This pose feels far more natural and establishes a connection between the figure and the viewer.

Instead of a rigid expression, her posture conveys calm and softness, which was highly unusual at the time. Her right arm rests gently on the armrest, while her hands are elegantly crossed. This twist in her pose and the positioning of her hands later became a standard in portrait painting, as artists adopted it to give their figures greater naturalism.

The Mona Lisa’s smile is undoubtedly the painting’s most famous feature – and it was groundbreaking in itself. Previously, faces in portraits were typically static and devoid of emotion. Leonardo, however, gave the Mona Lisa a subtle, ambiguous expression. His use of sfumato renders the smile elusive, as it appears to shift depending on the viewer’s angle: at times it seems warm, at others mysterious or even melancholic.

The term comes from Italian and literally means “smoky” or “hazy.” This technique involves blending transitions between colours and tones so smoothly that no sharp edges or lines are visible – much like how the human eye perceives light and shadow in reality.

The painting technique is most closely associated with Leonardo da Vinci. He achieved the effect by applying countless thin layers of glazes, each so delicate they were barely perceptible. Combined, these layers created a sense of depth and softness.

Until the Renaissance, figures in portraits were often reduced to their societal roles or symbolic functions. The Mona Lisa’s face, however, is realistic and unique, giving her a personal and human quality. Her eyes seem to look directly at the viewer, which was highly unusual at the time. This subtle “dialogue” between the figure and the viewer brings the portrait to life, creating an intimate connection.

The landscape in the background of the Mona Lisa merges seamlessly with the figure, giving it an almost surreal quality. Mountains, rivers, and skies fade into a hazy mist. The gentle transitions between Mona Lisa’s body and the landscape create a harmonious unity, making her seem like part of nature itself. With this technique, Leonardo expanded the picture space, creating a sense of depth that still draws viewers into the painting to this day.

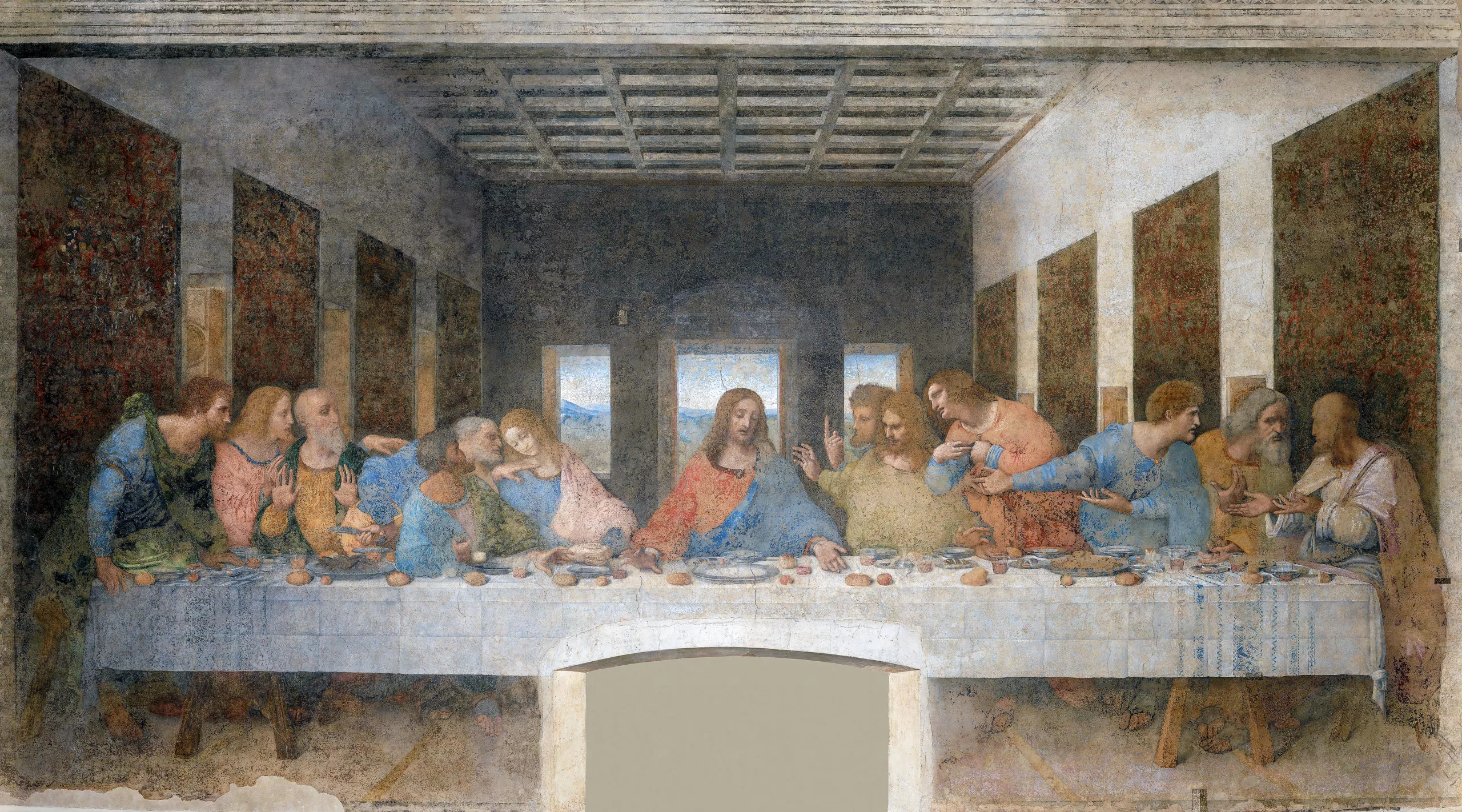

The Last Supper, created between 1495 and 1498 for the refectory of the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, is a masterpiece of dramatic composition. It captures the pivotal moment when Jesus tells his disciples, “One of you will betray me.” In this work, Leonardo masterfully conveys not just the external event but the inner turmoil of the figures.

Each of the twelve apostles reacts differently: shock, doubt, indignation, or anger – the emotions are so vividly depicted that the viewer feels as though they are witnessing the scene unfold. Unlike earlier depictions, where Judas was often isolated or placed prominently in the foreground, Leonardo integrates him into the group, intensifying the betrayal.

Judas holds a small purse in his right hand, an allusion to the thirty pieces of silver, and reaches for a piece of bread with the other. He is also the only disciple whose posture leans away from the central flow of the group. This subtle yet deliberate separation marks him as the betrayer – a revelation that needs no words.

The Last Supper | Leonardo da Vinci | Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan

Leonardo enhances the emotional impact of The Last Supper through his precise use of perspective. All the lines of the room converge toward the central point of the fresco – Jesus. He sits calmly at the centre, a striking contrast to the dynamic movement and gestures surrounding him. This composition not only guides the viewer's eye but also symbolizes Christ as the still, unwavering centre amidst the chaos.

Technically, The Last Supper was also an experiment. Instead of painting on wet plaster, as was standard for frescoes, Leonardo chose to work on dry plaster. This allowed him to refine details and create smooth transitions of light and shadow. However, the technique proved fragile, and the painting began to deteriorate quickly. Within a few decades, the first signs of damage were already visible. Despite numerous restorations and preservation efforts, the fresco remains heavily damaged to this day.

Many of Leonardo’s projects remained unfinished, yet this too is part of his legacy. His countless sketchbooks offer us a window into his extraordinary mind. His drawings of flying machines were inspired by the study of birds. He designed wings adapted to human arms, captivated by the possibility of conquering the skies. Centuries later, these concepts would inspire pioneers of aviation.

Leonardo also designed intricate machines, including catapults, armoured vehicles, and multi-barrelled guns – inventions that were far ahead of their time. He sketched plans for more hygienic cities, envisioning the separation of living and working spaces alongside sophisticated water systems to help curb disease.

His anatomical studies of humans and animals were among the most precise of his era. These detailed drawings of the human body were groundbreaking, influencing not only contemporary artists like Michelangelo but also scientists of the Enlightenment centuries later.

Through his sketches, Leonardo da Vinci created a vision of the future. His unfinished works bear witness to his relentless curiosity and drive. Never content with what he had already achieved, his vision propelled him forward – always in search of the next great idea.

Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo Buonarroti, and Raffaello Sanzio – three artists who shaped and, in their own ways, embodied the Renaissance. Despite their differences in style and approach, their works shared a common goal: the pursuit of a perfect union between humanity and the divine, nature and spirit. Together, they represent the soul of the Renaissance – an era driven by a quest for balance, expression, and knowledge.

Each of these three masters offered their own response to the questions of their time: What is humanity? How can the divine be depicted? And how can art make the world visible?

The three artists belonged to different generations, and their lives took very different paths. Their active creative periods overlapped primarily at the beginning of the 16th century, the golden age of the High Renaissance.

Leonardo was the eldest of the three and already a celebrated figure when Michelangelo and Raphael began rising in the art scene. While Leonardo reached the height of his career in Florence and Milan during the late 15th century, Michelangelo and Raphael were still young and finding their place. The two were close in age, belonging to the same generation, and their careers intersected particularly in Rome, where they worked on significant projects in the early 16th century under Popes Julius II and Leo X.

The relationships between the three artists were marked by both mutual admiration and rivalry. This dynamic pushed them to achieve their greatest masterpieces.

Leonardo and Michelangelo: These two giants of the Renaissance had a complicated relationship and were often seen as opposites. Leonardo was admired for his elegance, scientific precision, and calm refinement, qualities Michelangelo criticized as “too polished” and “lacking soul.” He found fault with Leonardo’s obsession with detail. Conversely, Leonardo, the thoughtful and refined intellectual, viewed Michelangelo’s raw, dramatic expressiveness with scepticism. It is said that the two publicly debated art in Florence – a rivalry that only spurred their brilliance further.

Michelangelo and Raphael: Michelangelo regarded Raphael’s harmonious style and success at the papal court with jealousy and suspicion. To him, Raphael’s works appeared too pleasing, too “simple.” Yet, Raphael admired Michelangelo and drew inspiration from him: the powerful figures in Raphael’s Stanze frescoes (such as the prophets in The School of Athens) clearly reflect Michelangelo’s influence.

Raphael and Leonardo: Unlike Michelangelo, Raphael looked to Leonardo’s work as a source of inspiration. He deeply admired Leonardo’s achievements and was strongly influenced by them. Leonardo’s impact is especially evident in Raphael’s depiction of faces and the spatial depth of his compositions. Raphael carefully studied Leonardo’s sfumato technique and incorporated it into his own portraits, giving them a refined, lifelike softness.

Florence, circa 1503–1506

Both were commissioned to create competing wall paintings for the Sala del Gran Consiglio in the Palazzo Vecchio: while Leonardo worked on The Battle of Anghiari, Michelangelo focused on The Battle of Cascina. Neither work was ever completed.

This direct competition is said to have further strained their already tense relationship.

Rome from 1508

Michelangelo and Raphael crossed paths in Rome while both were working for Pope Julius II: Raphael was painting the frescoes in the Stanze of the Vatican, while Michelangelo was simultaneously working on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Some sources suggest that Michelangelo believed Raphael had secretly studied his frescoes in the Sistine Chapel and incorporated elements of them into his own work.

Florence, circa 1504–1508

Raphael likely encountered Leonardo in Florence at the beginning of the 16th century. At that time, Leonardo was already an established master, while Raphael was still an emerging young artist. Though there are no concrete accounts of conversations or direct interactions between them, Leonardo’s influence on Raphael is unmistakable.

Lady with an Ermine | Leonardo da Vinci | Czartoryski Museum, Kraków

The shared legacy of these three artists lies in their liberation of art from rigid conventions. They created works that revealed the inner depth of humanity – its questions, desires, and its connection to nature and the divine. Their art was driven by the great themes of their time:

Humanism: Humanity moved to the centre – not merely as a reflection of the divine but as a creative and sentient being. Leonardo explored the human body with the precision of a scientist, Michelangelo celebrated it as an expression of strength and spirit, while Raphael presented it as a harmonious ideal.

Antiquity: All three drew inspiration from the classical world but reinterpreted it anew. Michelangelo brought the power of ancient sculpture to life, Raphael embraced its clarity and order, and Leonardo explored the proportions and natural laws that underpin it.

Progress: The Renaissance was also an age of knowledge and discovery. Each artist was a pioneer in his own right: Leonardo approached art analytically, making it a method for understanding the world. Michelangelo pushed the boundaries of material and form, while Raphael perfected the use of perspective, creating compositions of extraordinary balance that shaped generations of artists. Through his workshop, Raphael also set new standards for the teaching and transmission of artistic knowledge.

Together, they not only reflected the ideals of their time but also shaped the course of art history. They defined what art could be: a dialogue between humanity and the world, between past and future.

I could write endlessly about Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael – and still feel as though there’s more to say. Their works are so significant and layered with meaning.

But now I’m curious about your thoughts: What fascinates you about these three artists? Do you have a favourite work, or perhaps a special memory tied to one of their masterpieces?

I’d love to hear your perspective in the comments!

Join the newsletter now

and not miss a thing

Get exclusive insights into my creative processes, learn the stories behind my artwork

and receive invitations to my exhibitions and events.

To say thank you, I'll give you 10% off your first purchase.